As published in Vanity Fair (German Edition) October 12, 2008In Bali the spirits never sleep. From the mist-filled volcanic mountains of the north to the warm, turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean, up through emerald terraces of shimmering rice and into dusty villages of temples and laughing, bare-footed children, the Gods speak to the Balinese, normally with loving kindness, but sometimes with a loud and terrible fury.

In this land dubbed the “ Island of the Gods” it is important to pay heed to the spirits and deities. To perform ceremonies and rituals, to prepare offerings, to keep a fragile world in balance. There is magic aplenty here in Bali, if you have the eyes and ears for it. Ghosts sitting in the fork of trees, singing. Rain falling in temple grounds during the dry season. Black witches crossing the waters to darken people’s doors. To the Balinese what is unseen is just as important as what is seen. One must remain vigilant at all times.

Six years ago, just before the terrorist bombs ripped through Paddy’s bar and the Sari nightclub on Kuta Beach’s main tourist strip, killing 202 people from 22 nations, the Balinese received four warnings. They weren’t the kind of warnings normally associated with government intelligence agencies monitoring the activities of radical Islamist groups, although there was some of that too. No, these were the kind of alerts only a people deeply in touch with their spiritual and cultural traditions might have been able to see … had they been watching closely.

The first warning came two months before October’s carnage when a giant turtle was slaughtered on a beach near Klungkung, the ancient capital about 25 km north-east of Denpasar. The turtle, an endangered animal in Bali used for important ceremonies, was said to have had a swastika – the Hindu symbol for unity – naturally marked on its belly. Many Balinese now believe this turtle had come to save the island but instead of heeding the warning, a group of youths from a nearby village had killed it.

A week later a second warning was issued when, at midnight, in the temple of Klungkung, a wooden bell sounded. There was no one sounding the bell. On October 6, a third warning in the form of a white ring around the sun; and then, three days later, a fourth, this time a small earthquake shaking the region around Denpasar.

On October 12, 2002, exactly one year, one month and one day after the September 11 attacks on America, catastrophe struck in the physical world. Up in the palace in Krambitan, 35 kms from Kuta Beach, Rai Girigunadhi, a member of the most prominent royal family in Bali, thought he’d just heard thunder. “In my heart,” he told Vanity Fair last week, “I was happy. I thought it was the first rains of the wet season.”

He was horribly mistaken. A suicide bomber by the name of Iqbal had walked into the crowded Paddy’s bar on Jalan Legian, Kuta’s busiest street, and blown himself up, along with scores of foreign tourists. In a clever piece of evil a second bomber had been waiting for people to flee into the streets before he detonated a Mitsubishi van packed with more than a tonne of explosives. The van was parked across the road from Paddy’s, directly outside the popular Sari Club.

“Try and imagine the biggest wave you have ever known,” an Australian environmental student, Hannahbeth Luke, told me shortly after surviving the inferno, “and then multiply it by 1000. Imagine it breaking over you. All around you. The whole place exploding. I remember my body being lifted. I really thought I was dying. I thought `This is it,’ and then I realised I could move. And so I did. I ran like I’d never run before.

“Everything was hot to touch – dry heat, stench, my nostrils filled with smoke … I kicked my shoes off and began to climb. I remember grabbing these electrical wires and climbing up this four metre wall … and then I climbed over three garages and dropped onto shrapnel and glass and bits of metal. I landed without barely cutting my feet.”

Hannahbeth Luke’s English boyfriend, Mark Gajardo, had left the dance floor only moments before a song by British pop singer, Sophie Ellis Bextor, had begun blaring from the loudspeaker. The song – incredibly enough – was called Murder On The Dancefloor.

You’ll just have to pray

Don’t think you’ll get away

I will prove you wrong

I will lead you all astray

Stay another song I’ll blow you all away

Hey it’s murder on the dancefloor

Bodies were blown apart or incinerated on the spot, arms and legs and heads torn off, corpses charred and disfigured beyond recognition. Hannahbeth’s partner, Mark Gajardo, died near the entrance to the club while Tom Singer, a young Australian man whose life Hannabeth thought she’d saved, died a month later from his burns. He was one of 88 Australians murdered.

In the unfolding chaos people began running, screaming, bleeding, burning, vaporising, dying in their tracks, or in the arms of their rescuers. Hotel lobbies like the Bounty Hotel, 350 metres from the Sari Club, were suddenly transformed into emergency hospital wards. At one stage the hotel was confronted with the appalling fact that 177 of its guests were missing. By the time the dead and injured had been fully accounted for, 32 of the Bounty’s guests were dead and 48 injured.

“You cannot forget it,” the former manager of the hotel, Kossy Halemai, told me. “I think it will stay with me as long as I live.”

***

Three years after that dreadful night, on the evening of October 1, 2005, lightning struck a second time. Three bombs, one in Kuta Square and two at seafood restaurants on the beach at Jimbaran Bay, were detonated by three men wearing backpack bombs. Twenty people, many of them sitting at dinner, died in the attacks. The heart of Bali had been smashed again.

In the aftermath of the first bombing in 2002, as tens of thousands of tourists had fled the island, as hotels had emptied of their guests, as village after village had been thrown into poverty, as beaches and restaurants had been deserted, the Balinese had set about cleansing their island home – placing their special offerings, preparing exorcisms for the dead, whispering their mantras and prayers, spending what little money they had on trying to restore the cosmic order.

They had also done something else quite extraordinary. They had begun asking questions not normally posed by a people overwhelmed by grief. What had they done wrong to bring this calamity on their guests and themselves? Were they not sufficiently observant in their prayers? Had they strayed too far from their traditions, not been Balinese enhough in their daily practices? Had they been too busy looking after their guests to heed the warnings?

This was not to say they didn’t also start searching for answers in the temporal world, that they didn’t suspect Islamic militants for this unprecedented violation of their home. They did. It was just that as Agung Kartini, sister of Rai Girigunadhi, told Vanity Fair last week, the Balinese preferred to look at themselves first.

“Why should we blame others before we check ourselves?” this princess and priestess said as she sat with her brother in the fading glory of their family’s palace in Krambitan where Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall once celebrated their wedding. “We will look at everything that happened, but we will check ourselves first.”

***

Bali is a little dot in a swarm of islands in the Indonesian archipelago. It is a place of such loveliness that it almost takes the breath away. To visit it now, six years after the first bombing, three years after the second attack, is to find a society in the grip of an unexpected and extraordinary economic boom: Rice fields being razed for apartments and boutique resorts, villas being constructed on cliff faces, clubs offering all-night dance parties, new concepts in sophisticated fusion dining, spa treatment centres in the foothills and by the sea, fashion and furniture businesses flourishing, five star chains such as the Four Seasons, the Aman resorts, the Bulgari, the Intercontinental, the Ritz Carlton, St Regis … all competing for tourists from Australia, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, Europe, and the new high-rollers in town, the Russians. (Such is the Russian presence here that there are now even Russian restaurants, menus in Russian and Russian hospitality staff!)

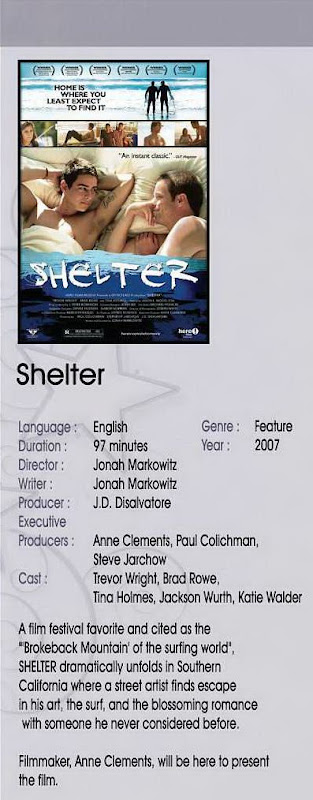

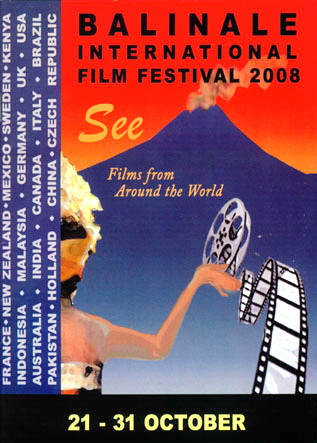

Last year delegates from over 180 countries flew to Bali for the United Nations Conference on Climate Change. In two weeks time (editors note October 14-19) some of the world’s leading writers will attend a literary festival in the central highlands of Ubud. At the same time Bali will also play host to a new international film festival.

“There is no way Bali is on the ropes,” says Australian expatriate, Made Wijaya, a resident of Bali for over 30 years and one of the world’s leading landscape gardeners.

“It’s barely even reeled from the punch.”

Tourist figures confirm this. By the end of July more than one million people would have visited Bali this year, making it the most successful year for foreign arrivals on record, far more than before the first bombing. Indeed at the time of Vanity Fair’s visit last week it was all but impossible to find a spare bed amongst the 40,000 on the island. Other than perhaps Dubai it’s hard to imagine a place on earth experiencing such spectacular economic growth.

And yet what makes Bali unique is that it remains a place of ceremony and ritual, a place deeply wedded to its communal and spiritual belief system.

“The wheels keep turning here as they have for centuries,” Made Wijaya tells me on a visit to his home in Sanur on the south-east coast. “This is not just a playground. It’s the world’s last surviving medieval God-kingdom.”

And therein lies a source of conflict - the clash between the commercial and the spiritual. On a clear day on the beach here at Sanur you can look across the Bandung Strait to the tiny island of Nusa Penida, known by tourists for its steep cliffs and spectacular diving locations. To the Balinese this is the home of Ratu Gde Mecaling, the supreme deity and protector of Bali who lives in the main temple.

In the lead-up to the 2002 bombing Nusa Penida was the proposed location for a gambling casino, despite widespread opposition from the local population and a number of priests. Although desperately poor, the people of Nusa Penida opposed the casino for fear it would provoke the fury of their protector.

According to Agung Kartini this is perhaps what happened. Why? Because the person behind the casino proposal was none other than Kadek Wiranatha, owner of Paddy’s bar, the first place blown up in 2002, as well as the Bounty Hotel which lost 32 of its guests that same night. Kadek Wiranatha also happens to own Indowine, the biggest distributor of alcohol on the island, not to mention the world-famous nightclub, Ku De Ta where Bono once gave an impromptu performance and where, in the last few years, people like Mel Gibson, Christine Aguilera, American soul and hip hop singer, Erykah Badu, and international model, Kate Moss, have come for cocktails by the sea.

During the European high season it is not unusual to find 2500 people in wild celebration, grooving to the latest dance tracks over the Indian Ocean.

Over lunch at Ku De Ta last week Kadek Wiranatha told Vanity Fair it was not he who had proposed the casino for Nusa Penida, but rather his brother and business partner, Gde Wiratha. Nonetheless he saw no problem with building such a complex there, so long as it was not built next door to the temple of Ratu Gde Mecaling. “If you want to build a casino on Nusa Penida, I think it’s possible,” he said. “Just find the right land.”

As Bali’s richest and most successful entrepreneur, Kadek Wiranatha told Vanity Fair that while he didn’t believe in magic – as most Balinese do – he did believe in the spirit world.

“I do believe in things I can’t see,” he said. “This land, for instance, where we are sitting having lunch (at Ku De Ta) is an old cemetery … and so I pray for the people who are buried here.” And this he says without a hint of irony.

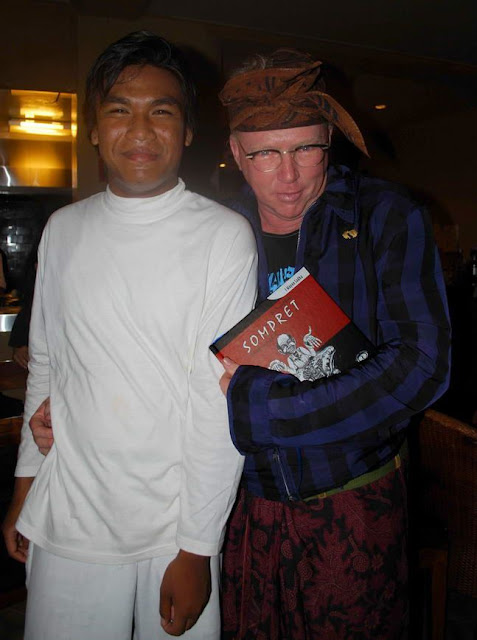

Rio Helmi, Vanity Fair’s photographer, believes this is this kind of approach to commercialism that can cause problems for Bali. The son of Indonesia’s former ambassador to Germany and a veteran of 35 years photographic experience in Bali, Helmi believes Kadek Wiranatha is stretching the bounds of what is possible.

“He lives on the fault line,” Helmi says. “He presents that whole brash culture which believes you can do anything you want. And that’s part of the anger that drove the bombers to do what they did. They wanted to hurt this place where it hurt most, and that’s why it was a perfect strike.

And yet visiting the area around Ground Zero near Kuta Beach one is struck today by the glorious, throbbing, defiant life force prevailing again in Bali: Hawkers plying their trade. Cafes, bars and restaurants jostling for business. And t-shirts on sale summing it up best: `Drop Pants Not Bombs,’ `Fuck Terrorists,’ `Osama Don’t Surf,’ and the one that Rio Helmi chooses to wear: `There is no Prophet in Terrorism.”

***

Sometime later this month (editors note October) on an island off central Java three men are likely to be led from their prison cells in the middle of the night, taken out into the bush and tied to poles or crosses, had black hoods placed over their heads and shot by firing squad.

The firing squad of 12 men will be assisted by a spotlight illuminating reflectors placed over each man’s heart. The men will be given a choice as to whether they want to die standing, kneeling or sitting.

This is the fate that most probably awaits three of the Bali bombers, members of Jemaah Islamiah, the radical Islamist organisation responsible for both Bali bombings.

Last month (September) the condemned men – Amrozi bin Nurhasyim, Ali Gufron ( better known as Muklas) and Imam Samudra - attempted to argue before a panel of Indonesian constitutional judges that death by firing squad amounted to torture. Instead of being shot and left to bleed to death for several minutes they preferred to be beheaded.

The Indonesian Government argued it was not torture to kill by shooting. “If they feel pain,” said the Justice and Human Rights Minister, Andi Mattalatta, “it’s just a natural process and it doesn’t contradict our constitution. Pain and torture are two different things.”

None of the three Moslem radicals has ever shown the slightest remorse for the death and devastation they caused here six years ago. Amrozi, a 46 year-old father of four and the man responsible for buying the chemicals and Mitsubishi van, came to be known as “the smiling assassin” for the way he laughed in court and gave the thumbs up when convicted.

In an interview following his 2003 conviction he admitted that his smile was his weapon because it made his enemies upset. “This is a very special weapon for jihad,” he said.

His brother, Muklas, a 48 year-old Islamic teacher, was found guilty of being the overall co-ordinator of the operation. His recruitment to Islamic militancy had begun in 1989 when he’d joined Arab mujahedin in Pakistan plotting ways of putting an end to the Soviet occupation of neighbouring Afghanistan. Asked by a judge if he knew Osama bin Laden from those days, Muklas had replied: “Yes I know him well,” but he denied Bin Laden had had any role in the Bali bombing.

The third convicted bomber, Imam Samudra, the 38 year-old so-called “field commander,” chose the target, led the planning meetings and then stayed behind in Bali for four days after the attack, to watch – and revel – in the carnage he created. He’d learnt about explosives in Afghanistan during the same peiord as Muklas and then, two months before the Bali bombing, studied tourist literature to narrow down the list of possible targets. All of them regarded Bali as a haven for Western decadence.

A fourth man, Ali Imron, the younger brother of Amrozi and Muklas, was also found guilty of his role in the bombing – he helped build the bomb that destroyed the nightclub – but was spared the death penalty because of his remorse.

In an extraordinary interview last year with Australian radio Ali Imron explained how he had been “de-radicalised” as a terrorist and was now helping Indonesian police break up terrorist cells. “I’m giving all this information to police so I can stop violence and terrorism,” he said.

Asked whether he ever thought of the people he killed on the night of October 12, 2002, Ali Imron replied: “Yes I’m still thinking about that night and the victims. Why did I commit that act of violence, that act of terrorism? What harm did those victims do? The mistake we made was that all along our target had been the US Army and its allies that have been waging war against Moslems. It was wrong to attack civilians. I will continue to ask for forgiveness from the victims and their families, from anyone affected by violence in which I was involved.”

The majority of Balinese remain unforgiving and would like to see the bombers executed. On this Hindu animistic island the threat of fundamentalist Islam has not gone away. Although extraordinarily tolerant towards their Muslim neighbours – said now to be more than 30 per cent of the population – they view with alarm proposals coming out of Jakarta.

Last week more than 1000 people gathered outside the Legislative Council building in Denpasar to protest against an anti-pornography bill - one that, if passed, could make it illegal to kiss in public or wear a bikini. Even statues of naked gods and goddesses, part of the great pantheon of Hindu deities, would have to be covered.

“We will continue to reject the pornography bill,” the Governor of Bali, Made Mangku Pastika, told the crowd. Pastika is the former police chief of Bali credited with capturing the Bali bombers. He was elected governor earlier this year.

The Balinese are a gentle but defiantly proud people. In 1906 the Dutch mounted a naval bombardment of the capital but rather than surrender the Balinese decided on the only honourable path – a suicidal puputan or fight to the death. As many as 4000 nobility, all dressed in their finest jewellery and waving their ceremonial golden knives, marched to their slaughter.

Over the centuries the Balinese have shown the world what it means to adapt and still be themselves. They have absorbed and withstood Hinduism, Islam, Dutch colonialism, Japanese invasion, Javanese transmigration, the massive corruption of the (former president) Soeharto years, tourism on a grand scale and, in recent years, terrorism. Still they flourish.

“I think Bali is just one long process of re-invention,” the Four Seasons’ general manager, John O’Sullivan, tells me finally, as we sit on Jimbaran beach watching a blazing sunset melt into the night sky. “Regardless of their circumstances they have an ability to go back to their spiritual essence. That’s why this is the most amazing place in the world.”

ends